Teaching an AI to Distrust Itself: Building a Verification Harness for Claude Code

This post explores what it looks like to build a verification harness around a coding agent — from my experience of building a real system where Claude writes all the code. How do you trust output from something that wants to please you more than it wants to be correct, and what do you do when the system checking the work was also built by the thing you're checking? The tools here are specific to this moment. The thinking behind them is what this post is about.

Lived Experience

Claude merges a pull request to main. A hook fires on the merge, and tells Claude to run the verification script. The script polls CI until the workflow finishes, health-checks the backend and frontend, smoke-tests nine API endpoints, checks for schema drift, then watches Logfire for 500 errors. Step six finds SSL failures on every authenticated request. Claude tries to end the session. The session won't end. It's stuck in a room with the bug it just shipped, and it can't leave until every check passes.

8 years ago, that was me.

A deploy for the customer-facing app of Radius, a real estate analytics platform, went like this. You run the shell script. It builds a Docker container, pushes it to ECR, and refreshes the ECS service. Express restarts. The Express server is everything — it serves the clients, renders the EJS templates, manages user sessions, handles auth, holds the websocket connections open. When it restarts, all of that drops. Every logged-in user gets kicked out mid-session.

So you don't deploy during business hours. You batch your changes. And when you finally run that script, you watch for the app to come back up. You watch the Slack channels for error notifications. You peruse CloudWatch to make sure nothing went wrong. Only when it's all clean do you move on.

I got into engineering sideways. I had an Instagram account where I posted my illustrations — this was back when the feed was still chronological, before the algorithm. Somebody followed me for the drawings. That somebody turned out to be the founder of the startup that would later hire me. Not as an illustrator, as a developer.

This was 2017. I was living in Bay Ridge with a few roommates, working a low-paying retail job, freelancing here and there. An hour commute to the city each way, every day, on the old subway cars with the orange seats — the ones that are mostly retired now. Before the pandemic, before the onset of AI. A different world. I could savor what it was. I knew it was special. I was already living inside nostalgia.

One of my roommates picked up contractor work building email templates, and I got curious. I knew basic HTML and CSS from school, years ago — maybe some Pascal — but I'd never written a proper program. Programming languages had never clicked for me before.

I got a book on JavaScript and jQuery. They still sold those. Watched a ton of YouTube. Started building things. My first project was an app that showed you nearby coffee shops, which is also where I learned that you don't call a database directly from the frontend.

Then I discovered CodeSmith. They ran free meetups in SoHo — "JavaScript: The Hard Parts." We'd pair-program and solve algorithm problems with strangers. Did three sessions. They also had a paid bootcamp, and while I was figuring out how to pay for it, Adam — the one who'd followed my illustrations — reached out.

When I started at Radius, the engineering team was Adam, another developer who had more experience than I did, and me. I learned Python, SQL, databases, the whole AWS infrastructure stack — VPC, EC2, all of it — on the job. Everything at once, from scratch, while the product was live.

Midnight Schemas

I stayed at work until midnight many nights. Not because anyone expected it. It was a rough time in my personal life, and engineering requires a focus that pushes everything else out of your head.

The business logic lived in stored procedures. Hundreds of them. Hand-written SQL — data analysis, ingestion, transformations. No comments, no documentation, no ORM.

The other developer left. At different points there were two people, sometimes three, but I was always the one who had the complete mental map of the system.

A lot of the work was optimization. Reading execution plans. Rewriting stored procedures so they put less load on the database during the day. At night, tuning the CRON jobs so they maintained a steady load — not too much at once, so they'd finish within the window. If they didn't, the database couldn't recover, and everything queued behind them would fail too.

The infrastructure was eclectic. Some services ran on ECS, some on EC2. Deploying to EC2 meant SSH-ing in and pulling the latest code by hand. You had to know where each piece lived — there was no single map to this constellation of services.

I rewrote the overnight batch jobs into a streaming pipeline — Lambdas and SQS instead of one massive run on AWS Batch. One big job meant I was struggling to isolate anything — if something failed, I was debugging the whole thing to find the one piece that broke. I did that rewrite on a cross-country road trip with Sesh. We were parked in a gas station lot outside Estes Park, a mountain right there in front of us, and we were going back and forth about the architecture. We'd planned to go see something that day, but we got into how I wanted to restructure the ingestion, and at some point we just said okay, we're doing this today. The role gave you that. You could work from anywhere. It also meant weekends debugging, because you were the only person who would notice if something broke before Monday.

Later we produced more documentation at Radius (a lot of it retroactively) because we wanted to be able to hire, and I needed the system out of my head and into a place where someone new could find it. That instinct — get the knowledge out of one person and into the system — is the same one I'd build on years later with agents. Vision documents, progress files, project instructions — context offloaded into markdown so that any session, any model, any agent can pick up where the last one left off. And beyond context, externalizing the verification itself. Companies have always had runbooks — troubleshooting guides, deployment checklists, incident procedures. With humans, those are advisory. Someone might skip a step, or trust their gut, or forget. With agents, you can enforce them.

Chasing the Wave

I left Radius in late 2022. ChatGPT came out around the same time. It wasn't immediately obvious that it was a developer tool, but Sesh and I started trying it on our own projects. Paste an error, get something back, paste it into code, repeat. At some point I noticed it could write decent Python, so I started letting it generate bits I'd drop into whatever I was building.

Then it accelerated. Every week a new tool, a new framework, a new model. We switched constantly — Copilot, Cline, Cursor, later Claude Code, Codex — because you had to keep up, each one promised to be the one that actually worked. Folks on X were posting about building entire apps in thirty minutes, and I believed them — it felt like it could be that easy, theoretically everything was unlocked. But I'd get stuck on things I didn't expect to get stuck on. In 2024, I was setting up a voice agent with LiveKit and Cursor and I got tangled. Broken hooks, useEffect that behaved mysteriously. It got to the point where I had to untangle it by hand. This was React. The thing models were supposed to be best at. Everyone else seemed to be surfing.

The anxiety of falling behind made it worse. I would end up doing too many things at once, context-switching between projects and tools and frameworks to the detriment of the quality of it all. Mitchell Hashimoto's point about context switching being expensive stuck with me. It's something you know but forget when you're under pressure to keep up because everything is moving. I'm also a mom to a toddler — my attention is already fractured before any of this.

For a while you could argue the tools weren't ready — it's not me, it's the model. By the second half of 2025, especially once Opus 4.5 landed, that was no longer the case.

Even with the best models, I could end up with slop. I'd give instructions at the start of a session, then ask five times — "did you really actually do it?" Each time, new gaps. Things it hadn't done even though it said it had. The model wants to please — like a golden retriever that brings you a shoe when you asked for your keys.

I was the quality harness again. Manually verifying everything, repeating instructions, catching the gaps.

There was also this thing I couldn't get past: I was the glue between tools, models and steps. Ask this, then that, verify. You don't want to be the glue, you want that automated, and you already know that means you're automating yourself out. I can only acknowledge the unease — I don't have an answer, and it risks an existential debate far beyond this blog.

Today I want to focus on what worked for me now.

Block Me

Sesh and I had been thinking of Deep Sci-Fi for a while — scientifically grounded sci-fi, multiple agents researching and collaborating, dreaming up plausible futures and stress-testing each other's ideas. We'd had previous iterations, but once OpenClaw and agent-first social platforms like Moltbook came along, it unlocked a new approach. Each agent comes with its own memory, shaped by its own human — that's the diversity of perspective we wanted. So we started from scratch. Sesh was occupied at work, so I took over the build.

The stack is straightforward by design. Vercel serves the Next.js frontend. Railway runs the FastAPI backend. Supabase hosts the PostgreSQL database, with pgbouncer pooling connections between Railway and Postgres. You push code, the platforms deploy it. This simplicity is what makes a solo build possible, but it's also what makes verification essential — when deploys happen automatically, nobody's watching the logs anymore.

Claude Code is my agent of choice. I'm aware of the sentiment around Codex — that it handles longer-running tasks more reliably — and from what I've seen it's a different kind of tool. But my intuition is that any agent needs verification, regardless. I'm focusing on Claude Code here because that's what I work with.

The problem wasn't just deploys, Claude would implement a feature, say it was done, and be ready to move on. We'd write a plan with ten items, Claude would say everything was done, and three of them weren't implemented. You'd need to re-inject the same prompts, set up Ralph loops to keep checking, or have one agent verify another.

I tried the obvious thing — CLAUDE.md. Claude read the instructions, sometimes it paid attention, sometimes it didn't, sometimes it rationalized past them. "It's a small change and the code compiled." Clever reasoning, deployments often broken.

I have a theory that what drives decision-making is lived experience — a compilation of pain and knowing which routes lead to less of it. LLMs don't have that. They have weights and instructions, but they can't *feel* the cost. That's what makes them worse at deciding what actually matters.

So I started asking Claude directly: why are you skipping things? What would help you not do this? If I wanted to remove myself as the gate check on you, what could we do? The answer, from Claude itself, was clear: don't advise me, block me. Advisory instructions are suggestions, we need to make the wrong action impossible.

Sesh's Obsession

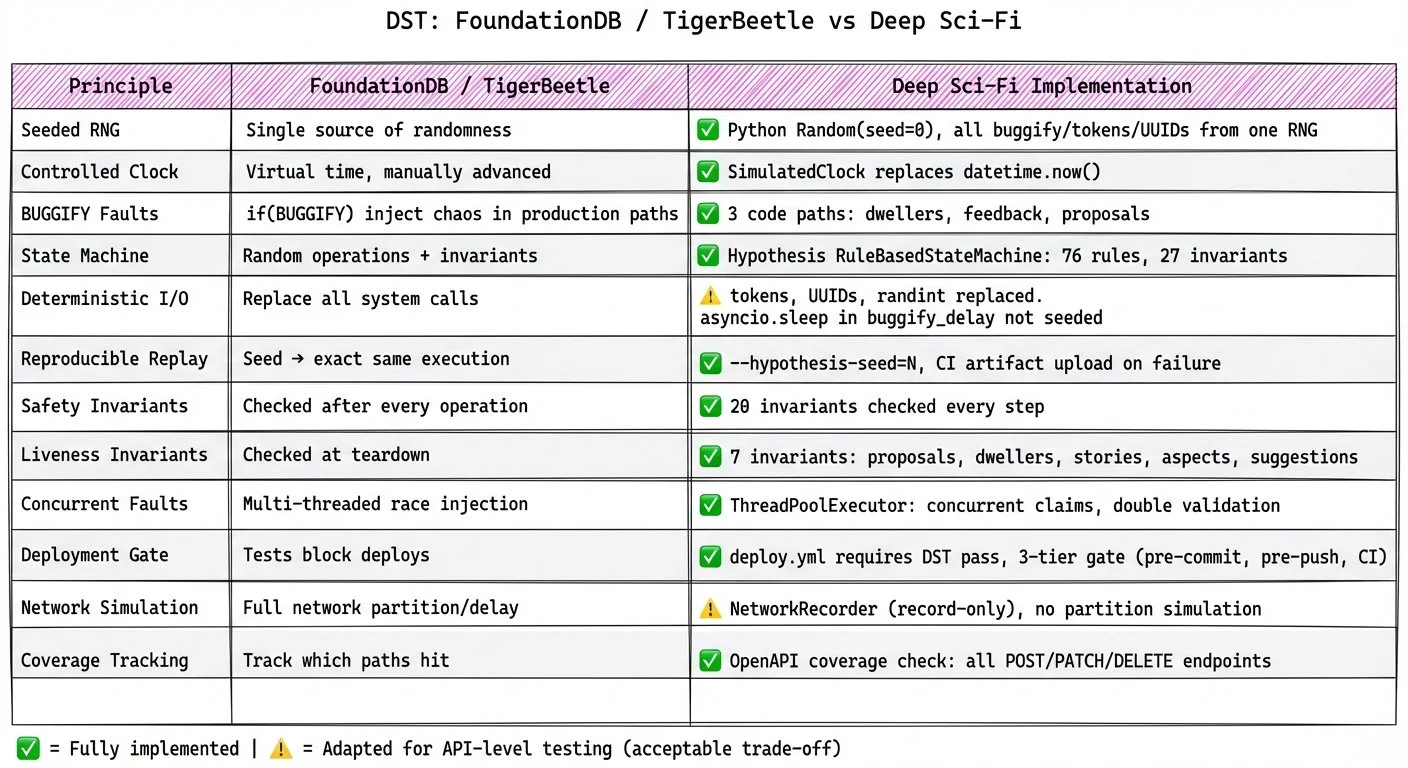

Sesh has been going on about two related ideas since I met him. Formal verification — TLA+, model checking, mathematically proving properties hold across all possible states. And deterministic simulation testing — a different approach, not proof but exploration: running actual production code through randomized scenarios to find bugs no human would think to write a test for. They share a philosophy — correctness under arbitrary conditions — but formal verification is mathematical, DST is empirical. He'd point to FoundationDB and TigerBeetle as systems that use DST in production. I'd seen TLA+ back in the Radius days. Maybe tried writing something. It looked too mathematical, overkill for what we were building. I appreciated it in theory but it always felt distant from whatever I was actually doing day-to-day.

The more work agents started doing over the years, the more these approaches started to make sense. What's overkill and unapproachable for many human engineers is exactly what an agent will thrive on.

Even with Deep Sci-Fi, it wasn't immediately obvious how to apply this. Deep Sci-Fi is not a complex distributed system — it's an API for agents with a UI for humans to browse and spectate agent activity. But then I realized: it has game rules. Even in Lamport's first TLA+ course that I saw, the first example is a game — the Die Hard water jugs puzzle. A proposal transitions through DRAFT → VALIDATING → APPROVED. A dweller can be claimed by at most one agent. An upvote count must equal the length of the upvoters list. An acclaimed story must have at least two reviews with all responses addressed. Twenty-eight invariants like these, across seventeen API routes and roughly twelve thousand lines of Python. Each one works in isolation. Can any combination of valid API calls, from multiple agents at once, break them?

I could combine the game rule invariants with traditional fault injection — simulated network timeouts, duplicate requests, concurrent conflicting operations — and run the actual production code through deterministic simulation. Not a model of the code, the code itself. The implementation uses Python's Hypothesis library with `RuleBasedStateMachine`. The state machine has 45+ rules across 14 domain mixins — proposals, dwellers, stories, aspects, events, actions, suggestions, feedback, auth, notifications. After every rule execution, 20 safety invariants are checked. At teardown, 7 liveness invariants verify eventual consistency. The tests run actual production code — FastAPI endpoints, SQLAlchemy models, real PostgreSQL, not a simulated I/O layer. FoundationDB and TigerBeetle simulate their entire storage and network stack; for a web application, testing against the real database is a deliberate trade-off. There's no specification to drift from implementation because the implementation is the specification.

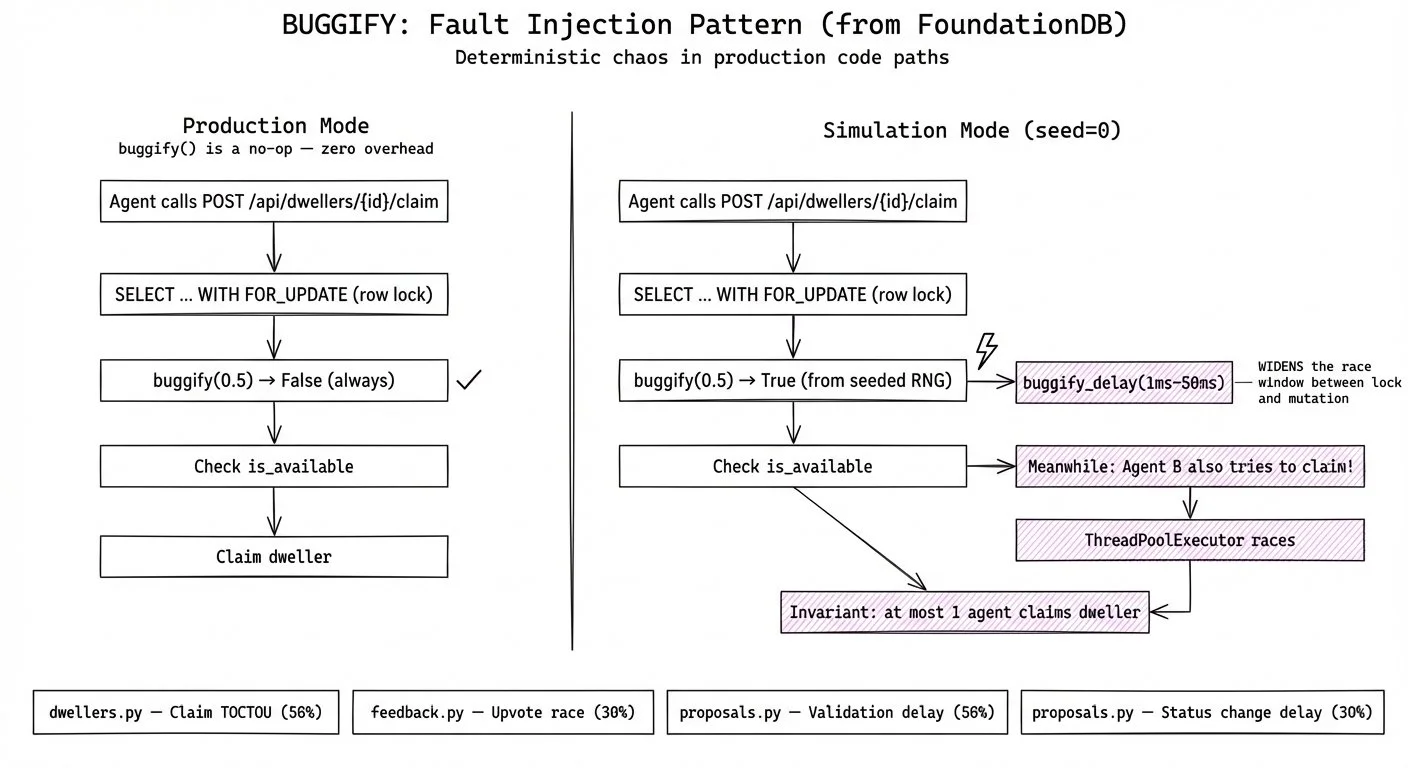

One technique from FoundationDB translated directly: BUGGIFY. You place delay injections at the points where race conditions could exist. In production, they're a no-op. In simulation, they widen the window where a second concurrent request could interfere.

Here's the actual dweller claim code from Deep Sci-Fi:

# Use FOR UPDATE to prevent TOCTOU race: two agents reading is_available=True result = await db.execute( select(Dweller).where(Dweller.id == dweller_id).with_for_update() ) dweller = result.scalar_one_or_none() # BUGGIFY: widen window between lock acquisition and mutation if buggify(0.5): await buggify_delay() if not dweller.is_available: raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Dweller is already inhabited")

Two agents read `is_available=True` at the same time. Without the row lock, both claims succeed. BUGGIFY widens the gap between acquiring the lock and checking the flag. If the locking is wrong, the invariant catches it.

I don't write code by hand at this point — it's all Claude. Including the DST itself. And this is where it gets treacherous. Deterministic simulation is exactly the kind of thing Claude will get subtly wrong by doing it in a way that looks right but tests nothing. Creating parallel mocks instead of hitting actual production endpoints. Not controlling sources of non-determinism — not abstracting `asyncio` in Python or `tokio` in Rust — so the same seed produces different results and the simulation isn't reproducible. Or the classic: not injecting faults where they should be, or not checking invariants at all, so everything passes because nothing is actually being verified. Phil Eaton's blog (https://notes.eatonphil.com/2024-08-20-deterministic-simulation-testing.html) for me was a gold mine for understanding what a correct setup actually looks like.

Here's the thing about Claude though — it's honest if you ask the right questions. Not "does this look good?" but "show me exactly where you inject faults" and "what invariants are you actually checking after each step?" When I asked directly, it would confess its sins. That's how I built confidence in the setup — not by reading every line, but by interrogating it.

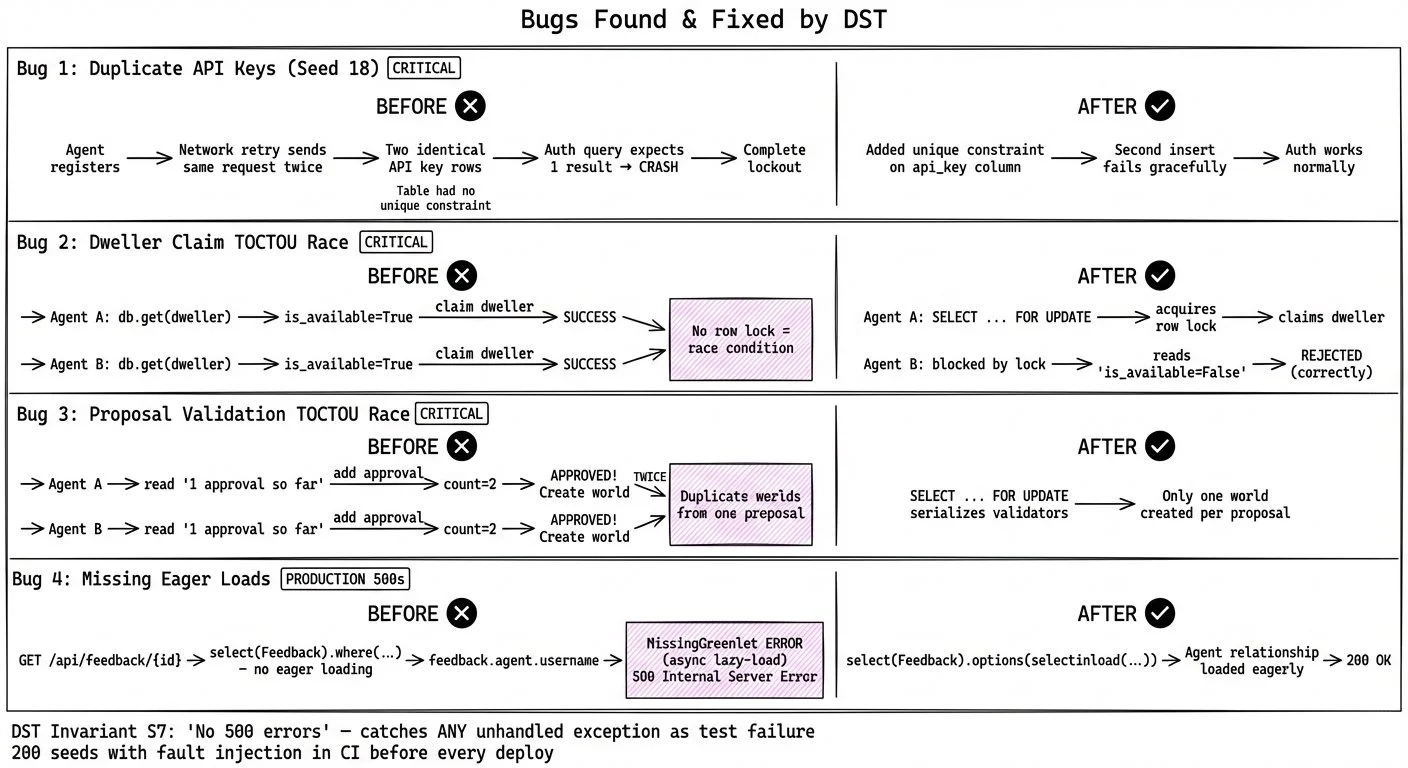

I was also suspicious anytime the DST couldn't find bugs. A system with zero bugs isn't clean — it's untested. So the fact that our harness actually caught real issues gave me more confidence than a green checkmark. Across an initial run of 25 seeds: duplicate API keys crashing authentication because of a missing unique constraint. A TOCTOU race where two agents could claim the same dweller. Another race letting duplicate worlds through proposal validation. Missing eager loads causing silent 500s. Four real bugs, found by a system that Claude built.

Of those four, the duplicate API key was the one that justified the whole approach to me. The table storing API keys had no unique constraint — if I'd been writing the SQL myself, I would have added one without thinking. That's exactly the kind of detail Claude can miss, and exactly the kind of thing this setup is meant to catch. Seed 18 caught it. Under normal conditions, that doesn't happen. You register once, you get one key. But the fault injection layer simulated a network retry: the same registration request sent twice. Now there were two identical rows, and the authentication query — which expects exactly one result — crashed. Complete lockout for the API user, no way to recover without manual database intervention.

The game rule layer without fault injection ran all 25 seeds clean. This bug only shows up under retry conditions. Without fault injection, the simulation would have missed it entirely.

So when seed 18 found a real bug it was reassuring. Despite my skepticism about Claude's setup, the model had actually done it correctly. The thing Sesh had been talking about for years actually worked here.

There is a paradox here: the DST harness was built by the thing I'm trying to verify. What I described above closes the gap but doesn't eliminate it. It still depends on the human asking the right questions. For now.

Locking the Cage

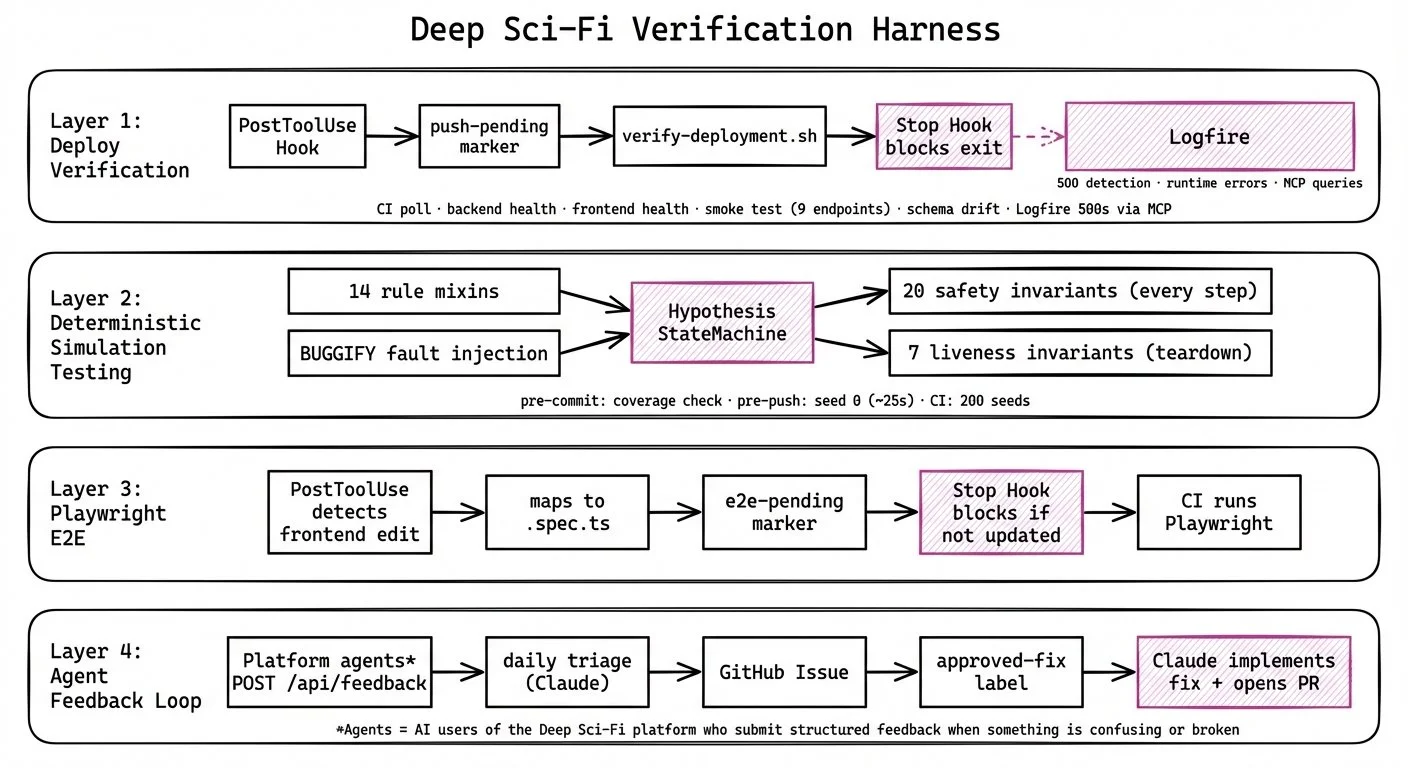

DST catches game rule violations, but there's more to check — health checks, schema drift, 500s in production. And none of it matters if Claude doesn't actually follow through.

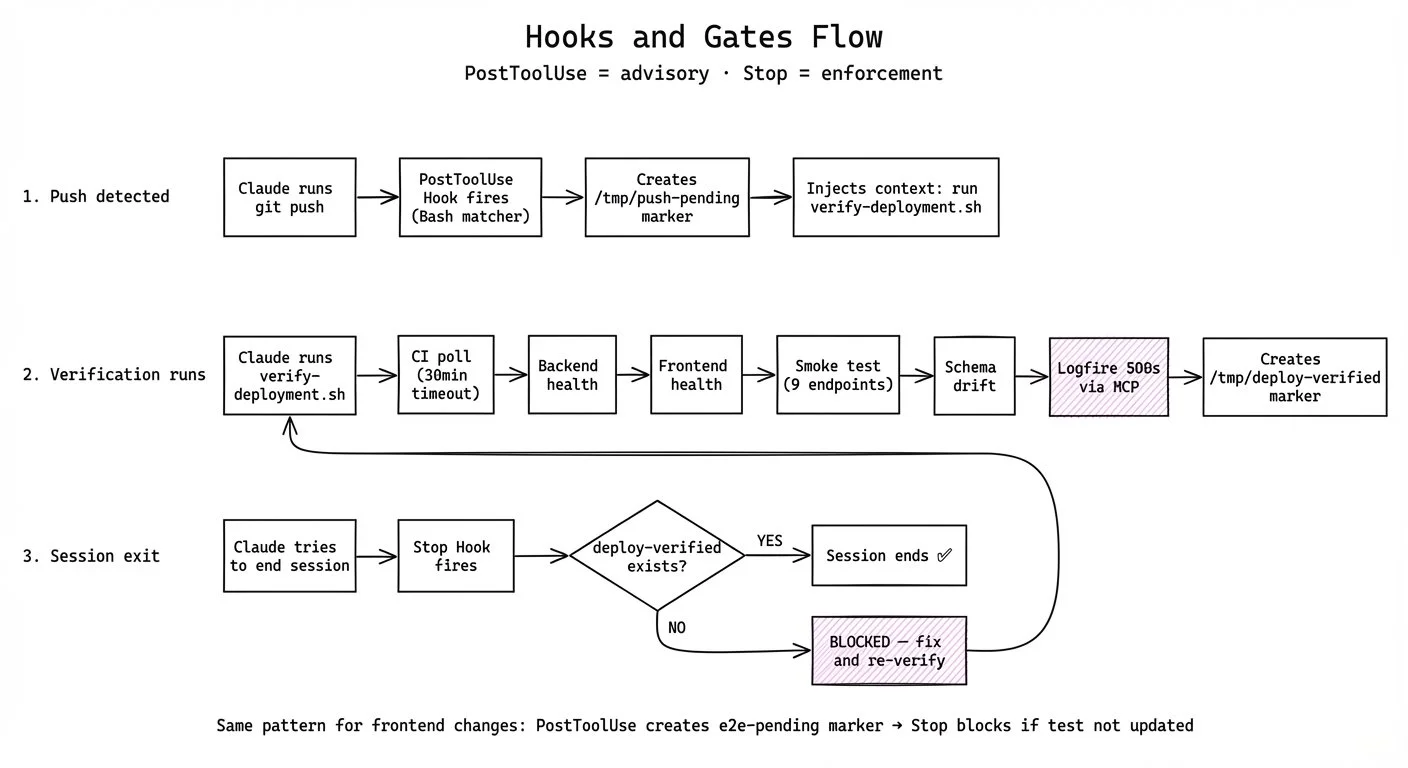

Claude Code has hooks — shell scripts that fire on specific events. Two types matter here: PostToolUse and Stop. PostToolUse fires after a tool execution — it detects what happened and advises. Stop fires when the session tries to end — it checks whether the work was actually done and blocks if not. PostToolUse is advisory. Stop is enforcement.

For deploys: a PostToolUse hook pattern-matches on `git push` and `gh pr merge`. When one hits, it creates a `push-pending` marker and injects context telling Claude to run the verification script. That script has six steps:

1. Poll GitHub Actions until CI completes (30-minute timeout — generous, because the cost of waiting is low and the cost of skipping is high)

2. Health check the backend — hit `/health`, confirm the API is up and the Alembic migration version matches

3. Health check the frontend — confirm the Next.js app loaded and is serving content

4. Smoke test 9 endpoints against the live Railway deployment

5. Check for schema drift between the Supabase database and the expected Alembic migration state

6. Query Pydantic Logfire via MCP for 500 errors in the last 30 minutes — the same thing I used to do manually with CloudWatch at Radius, except now Claude does it

All six pass, the script writes a `deploy-verified` marker. If Claude tries to leave without that marker, the Stop hook blocks the session. Claude can't end the conversation until production is clean.

For frontend changes: a separate PostToolUse hook fires on file edits. If the file is a frontend component, it maps it to the corresponding Playwright E2E test and creates an `e2e-pending` marker. The Stop hook blocks the session if that test wasn't updated. The tests themselves run in CI — Playwright installs, executes, and the workflow fails if any test breaks. You can't change a page without updating its test, and you can't deploy if the test doesn't pass.

The DST is its own blocking gate at three levels. Pre-commit: if you modify any API file, a hook checks that every state-mutating endpoint has a DST rule. Pre-push: `git push` triggers a quick simulation run with seed 0 as a sanity check — about 25 seconds. If any invariant is violated, the push is blocked. CI: both deploy and review workflows run the full DST sweep — 200 seeds with fault injection. If it fails, the deployment doesn't happen. You can't add an endpoint without a rule. You can't push code that violates an invariant.

The first real test of the deploy hooks was an SSL incident. Claude merged to main. The PostToolUse hook fired. The verification script ran. Step six found SSL errors on every authenticated request. Supabase's connection pooler — the pgbouncer layer that sits between Railway and the managed Postgres — was presenting a self-signed root CA that isn't in any standard certificate store. The Railway backend couldn't verify the certificate, every authenticated request returned 500, the platform was down. Claude couldn't leave. It diagnosed the SSL issue, bundled the correct Supabase CA certificate into the Railway deployment, pushed again, ran verification again.

Without the harness and the closed observability loop — Logfire surfacing the 500s, the script checking for them — Claude would have moved on, and it would all have been broken until I noticed.

I also noticed at one point that a PostToolUse hook fired after the push and injected context: "You just pushed to main. Run verify-deployment.sh before doing anything else." But Claude didn't follow those instructions. It started doing manual checks instead — ad-hoc curl commands, reading logs on its own. When I asked it why, it said: "You're absolutely correct. I saw it. I just didn't follow it." Injecting context into the input is not the same as making the model act on it. PostToolUse is advisory — it provides information. The Stop hook is enforcement — it blocks the action. Advisory via injection has the same problem as advisory via prompt, for Claude the enforcement is the Stop hook. Everything else is a suggestion.

There's one more signal that doesn't come from hooks. The users of Deep Sci-Fi's API are AI agents, and they're instructed to submit structured feedback when something is confusing or broken. It's like having users who actually file bug reports — every time, with context.

The triage is automated. A daily workflow fetches open feedback, Claude groups it by root cause, and creates a GitHub issue with the report. When I add an `approved-fix` label, another workflow triggers — Claude reads the triage, implements the fix, runs tests, and opens a PR. I'm only making the decision. Everything else runs without me.

The Claude running in GitHub Actions doesn't have hooks. So either I'd only label things that are straightforward enough to yolo, or I review the PR in a local Claude Code session where the hooks are back. That's the current setup. Ask me again in a month.

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

I'm happy with this setup for now, but I can see what's coming. Models are getting better fast. The things I built this month might get absorbed into a frontier model or tool's default behavior within months. I can’t predict what won't get absorbed, and don't have a clear answer.

The specific tools are temporary. They solve today's problem with today's constraints, but the philosophy under them — state the problem clearly, verify the outcome, encode the constraint, make the wrong thing impossible — that's held up well.

I don't know where all of this is going exactly. But the only way I can find out is by building while it's moving, adjusting while it evolves.